748. JOE FRAZIER VS JERRY QUARRY

HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP FIGHT

JUNE 23, 1969

MADISON SQUARE GARDEN

QUALITY OF PLAY—7.92

DRAMA—6.95

STAR POWER—8.52

CONTEMPORARY IMPORT—7.88

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE—6.73

LOCAL IMPACT—6.27

TOTAL: 44.27

“FOOL IN THE RING”

If Tom Joad had been a rangy and tough amateur fighter, he would have been Jack Quarry, a Texan with “Hard Luck” tattooed on his knuckles who made his way west during the Depression in search of a better life for his family. He settled in Bakersfield, California, where he raised, and managed, a boxer who transcended his hardscrabble upbringing to—almost—reach the top of the fight game.

As that boxer, Jerry Quarry, put it, ’'My heritage was The Grapes of Wrath.”

Quarry was a solid heavyweight in an era of superstars—Ali and Frazier and Norton and Foreman, which was bad luck for him. But he was white, which was better fortune—Quarry was literally called “The Great White Hope” in the media, and got opportunities other, equally talented but non-caucasian fighters didn’t.

At just 195 pounds, Quarry didn’t scare the big boys physically, but he was an excellent counterpuncher and sported a mean left hook. And, adhering to the cliche about Irish fighters, he was extremely tough. Jerry was also very good-looking for the trade, with the wavy hair of a movie star and a twinkle in his eye. Unfortunately, he was a bad bleeder, which tended to offset his chiseled features with ugly shades of scarlet.

His combination of ethnicity, pulchritude, bravery and talent made Quarry an extremely popular fighter, and during the period when Muhammad Ali was absent from the ring due to his persecution by the U.S. government, the sport badly needed the Californian. “Quarry had an appeal that made the public snap up tickets,” Joe Frazier said. “Why not? He was a good-looking Irish kid with a nice smile and an engaging boy-next-door manner.”

He shot up the ranks, and when Quarry beat the 1964 Olympic champ, Buster Mathis, the victory put him in line for a shot at the title. At least, the portion of it that existed with Ali mostly out of the picture, but still considered by the public (and even by some official organizations) as the heavyweight champ. The next most legitimate contender was “Smokin’ Joe,” that is, Frazier, the steam engine out of Philly, and the two were paired off in a battle for the “Non-Ali Division” Heavyweight Championship belt.

The fight went down at Madison Square Garden on Monday night, June 23, 1969, in front of 16,570 fans. On the undercard was the heavyweight champ from the 1968 Mexico City Games, making his pro debut—George Foreman. After waving an American flag in the ring, George clubbed out a Brooklyn fighter named Don Waldman in the third round.

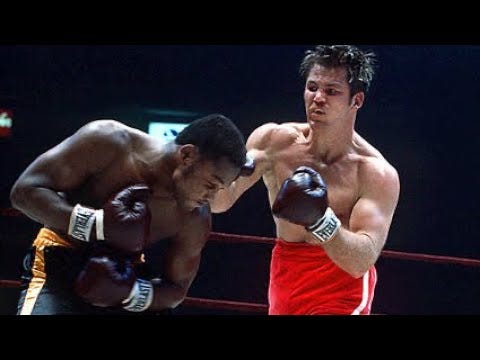

The crowd enjoyed the fight but wanted more bloody action, and Quarry was there to provide it. Smokin’ Joe was a similar brawler, with an even better (probably the best ever) left hook, but he was much stronger and craftier than Quarry, who entered the ring wearing a pink mandarin robe, a blue golf hat and a wide smile. Ironic California “peace, maaaan” vibes emanated off of him, screaming “Summer of Love” and Haight-Ashbury, and alas, Frazier was the hippie-pounding beat cop awaiting him with a billy club.

The two fighters went all out from the opening bell, engaging in a classic first round that saw both fighters score with enormous blows. The “Bellflower Bomber” unleashed multiple big lefts, but Frazier didn’t back down, and it was clear early on that Jerry couldn’t hurt Joe.

By the third round Frazier controlled the action, opening gashes all over Quarry’s face, in particular a spurting wound under his right eye that his corner struggled to control. Frazier attacked the area, closing the eye, and soon Quarry was able to see only to his left, a philosophically indefensible position when your opponent is throwing left hooks at your right eye. “Damn, Yank,” Frazier said to his manager, Yank Durham, after walloping Quarry all over the ring, “that man sure do have an iron chin.” For some reason, even though Jerry admitted to the ring doctor he was down to half vision, the medic let the fight continue for a seventh round. It was, literally, a bloodbath, as Quarry left his mud all over the Garden canvas. Both fighters bcame soaked in Quarry’s Type A.

“I wanted to go out on my back, like a man,” said Quarry, but the ref, Arthur Mercante, wouldn’t let him, at last stopping the fight before the eighth round began. “Like a stray hit by a car and not knowing where to go,” wrote the great Mark Kram in Sports Illustrated, “Quarry stumbled blindly about the ring after the doctor's decision, his frustration and disgust visible in every quiver of his muscles. Then he stopped and prayerfully looked up at the ceiling, his face a weird mask melting in the yellow light, mirroring, it seemed, his rage at the path of disaster he had chosen.”

AFTERMATH:

Quarry’s most famous fight came in 1970, when, alone among contenders, he agreed to fight Ali after Muhammad sued his way back into boxing. The bout in Atlanta once more was decided by Quarry’s propensity to bleed—a nasty cut gave Ali a third-round TKO.

Five years after meeting Frazier at MSG, the two fighters battled again, this time in Albany, N.Y., at the State Armory, an unusual site for such a fight. Smokin’ Joe again pulverized Irish Jerry, cutting him up and forcing referee Joe Louis to stop the fight in the fifth round.

Quarry’s lack of defense and repeated returns to the ring long past his glory days resulted in an unusually severe case of that fighter’s bane, dementia pugilistica. By his early-forties Quarry could no long feed or dress himself, and needed full-time care. “He hallucinates, he hears voices,” his brother James said in 1995. “When he walks off, we have to go find him. Sometimes we can't find him, and we have to call the police and they bring him back.”

Quarry died in 1999 after complications of pneumonia, aged 53. Despite it all, he never fully escaped the fate of Tom Joad.

WHAT THEY SAID:

“Only a fool has no fear in the ring, and he does not survive. Fighters seldom think about being noble and brave, and it is even more rare when one is genuinely unafraid of what the ring is, what it can do to the heart and mind and body. The professional, who knows what he is about, what his work is, and then—with all his fears and all his doubts—coldly does what he has to do, he will last and, if he is good enough, he will be remembered a long time. Nobody will ever again say Jerry Quarry is not a brave man, but he is not a professional and certainly, for one long, painful moment in his career last week, he lamentably insisted on being a fool.”

—Mark Kram, Sports Illustrated

FURTHER READING:

Flaunt It and You May Lose It by Mark Kram, Sports Illustrated

VIDEO:

747. NEW YORK ISLANDERS VS NEW YORK RANGERS

PATRICK DIVISION FINALS

GAME ONE

APRIL 14, 1983

NASSAU COLISEUM

QUALITY OF PLAY—6.84

DRAMA—6.49

STAR POWER—7.45

CONTEMPORARY IMPORT—7.25

HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE—7.31

LOCAL IMPACT—8.94

TOTAL: 44.28

“THE BALLAD OF BATTLIN’ BILLY”

As a diehard Islanders fan during the Dynasty Years, there was really only one fear—losing in the playoffs to the Rangers. Losing to literally any other team, even not making the postseason at all, was preferable. This was no doubt exacerbated by the fact that I was living in Rye, N.Y., the practice home of the Blueshirts, and a burg that housed many Rangers, at least during the season. This further led to my town being comprised almost entirely of Rangers fans, many of whom wanted nothing more than to derail the Isles string of Stanley Cups—in some cases, even more than they wanted to win their own title. Ergo, every matchup was particularly fraught, and in the postseason, that fright was increased exponentially.

The 1979 loss to the Rangers was excruciating; fortunately, the Isles got revenge in 1981 and 1982, en route to championships. In 1983, the three-time champs were eyeing a fourth consecutive title, even though the Philadelphia Flyers finished first in the Patrick Division, ten points ahead of New York. But there was always the skate blade of Damocles hanging over the proceedings, as the Rangers were out there, waiting to play spoiler even as they finished fourth in the division.

Sure enough, in the first round of the Patrick playoffs, the Rangers crushed the Flyers in three straight, scoring nine goals in the elimination game, leaving Islanders fans shaking their heads. Meanwhile, the Isles eased by the Caps in four, winning in straight sets, 6-2, 6-3, at the Cap Center after splitting a pair on the Island.

So for the third consecutive season, a Stanley Cup run would have to go through the most hated rivals from Rye. Counting the original 1975 encounter, stunningly won by the expansion Isles, this would be “Expressway Series V” and was breathlessly covered in the media as such. The Islanders were also on a 13-series playoff winning streak, and besting the Rangers would give them the all-time NHL record. Needless to say, the Manhattanites were eager to be the team that halted them.

To do so, they would have to best the man in the Islanders net. “Battlin’” Billy Smith was the mainstay in goal after the Isles snagged him from the Kings roster in their inaugural expansion draft. He wore the Blue and Orange for 18 seasons, encompassing their mercurial rise to the top of the sport and their incipient downfall as well. Smith was also known around NHL circles as “The Woodchipper” for his consistent predilection for slashing away at enemy skaters who dared enter his crease (or, more accurately, his swing radius). Smith accrued 475 penalty minutes in his career, second among goalies only to the fiery, possibly disturbed Ron Hextall on the all-time list. But Smith knew when to cool it. “When have I ever done something stupid in a big game?” he once asked rhetorically. “There’s a time and a place for everything.”

Smitty was also a sensational goaltender. He had won the Vezina Trophy the season before, and in 82-83 his goals-against average and save percentage were better than in his award-winning campaign. He allowed the fewest goals in the NHL. So the Rangers knew they had a tall task ahead when Smith skated between the pipes for Game One, held at the Nassau Coliseum on Thursday night, April 14, 1983.

But the start was quite promising for the city folk. The Rangers got an early goal from Ron Greschner to take a 1-0 lead. Early in the second period came the decisive moment. Ron Duguay and Mike Backman burst in on a two-on-none breakaway, with only Smith there to prevent a two-goal lead. “You do it in practice all the time,” Smith said about the two-man break. “You never see it in a game.” But there were Duguay and Backman, bustin’ in on his net. Smith spread out as wide as he could, abandoning his usual forward bend, with his glove opening and closing.

“You can’t guess,” Smitty said afterwards. “I tried to spread as wide as I could, play the angle best as I can…and hope it hits you.”

Duguay had scored 40 goals in 1981-82 but suffered through a woeful ’82-’83, which may have played into his decision to pass the puck. He passed early, maybe a shade too early, and Backman’s shot caromed off a sprawling Smith’s left leg. “I wanted to put it upstairs and I didn’t get good wood on it,” admitted Backman. The Isles were still breathing. Moments later Anders Kallur tied the game. It stayed 1-1 after two periods.

The home team busted it open in the final twenty minutes, as they were wont to do in this era. Denis Potvin blasted a 20-footer past Ed Mio to put the Isles ahead. The Sutter brothers, Duane and Brent, then combined on a pair of goals, with each bro scoring, to make it 4-1 and ice (yes, I wrote that…) the game. Bob Bourne assisted on all three of the latterly goals.

The Rangers had had a golden opportunity to steal the opener in suburbia and tilt the series in their direction. But Smitty got in the way, and the Isles led one game to zilch.

AFTERMATH:

The series was, as usual, a tight one between the two rivals, accentuating Smith’s early heroics. The Islanders eventually won in six games, breaking the record with their 14th-straight playoff win. The fishermen from Nassau County went on to win the Stanley Cup for the fourth straight season, a task that seemed much easier once the Rangers were dealt with.

WHAT THEY SAID:

“It turned the whole game around.”

—Ron Duguay, on the early 2-0 missed opportunity.

FURTHER READING:

Rangers Vs Islanders by Stan Fischler and Zachary Weinstock

VIDEO: